Music, in its various forms, has done quite well in the age of copyright. Digital technology has brought with it many tipping points, when old certainties give way to chaos before finding new stable states.

Any new stability will rely, as copyright always did, on some strong ideas to act as a foundation on which we can share music efficiently and fairly with each other.

We know what the old ideas looked like. Copyright is mysterious and complex enough to have its own creation myths which set the tone for the codes that followed them. One of the most romantic of these concerns the earliest surviving manuscript written in Ireland, a copy of a Psalter, ‘made in haste by night in a mysterious light’. The King is said to have ruled with the rustic phrase, ‘to each cow its calf’, that the owner of the original kept title in the copy. This is an elegant statement of the parental ideas behind the droit d’auteur and moral rights as any.

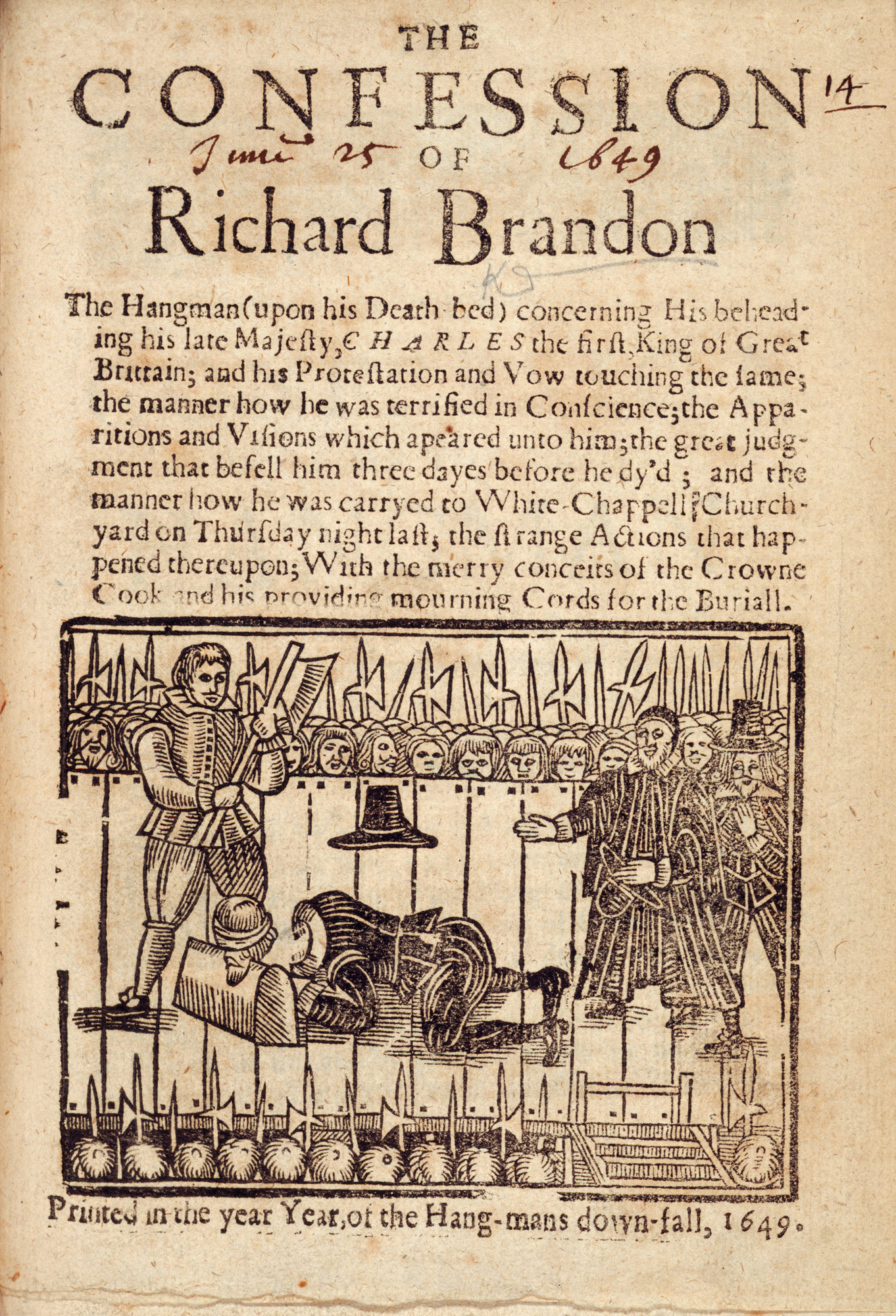

Other myths more prosaically bind copyright to printing monopolies and exclusivities granted by the 15th century Venetian senate. In mid 17th England similar monopolies granted by the king rather lost their force. The English Commonwealth was a regime that shut theatres and banned dancing on Sundays, an authoritarianism which saw copyright as a tool of political control, perhaps spurred by fear of the power of the pamphlet which had played so effective a part in the breakdown of the old order.

Other myths more prosaically bind copyright to printing monopolies and exclusivities granted by the 15th century Venetian senate. In mid 17th England similar monopolies granted by the king rather lost their force. The English Commonwealth was a regime that shut theatres and banned dancing on Sundays, an authoritarianism which saw copyright as a tool of political control, perhaps spurred by fear of the power of the pamphlet which had played so effective a part in the breakdown of the old order.

The regime was rewarded by a powerful blast from no less a voice than John Milton, poet, moralist and political activist. Areopagitica was issued as a pamphlet to argue for the repeal of the 1643 Licensing Order, which Milton saw as an attempt to bring printing under government control. State censorship exercised through the printing press was, said Milton, tantamount to:

the discouragement of all learning, and the stop of Truth

Milton failed in his campaign. And this was the backdrop to the Statute of Anne at the beginning of the 18th Century, which was either a shoddy backroom deal between publishers and government, or an enlightened recognition of the natural rights of authors, depending on your tolerance for conspiracy and progressive optimism respectively.

And so it remained for 300 years, with an ebb and flow between a strong sense of the fairness of giving creators control and reward, a continuing suspicion of corporate and commercial monopolies, and a general acceptance that the public too, expressed through access rights and term limits, has a stake in the game.

This tension is even found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The two clauses of Article 27 are hard to reconcile:

(1) Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific

advancement and its benefits.

(2) Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

The UDHR is a powerful statement of the rights of the individual which it seeks to protect when there might be a threat from cruel or repressive states.

The primacy of the individual however is far from being a universality in copyright just as in the rest of human history. Mark Rose has argued cogently that until there was a grant of rights to the author as an individual there was little expectation of originality and therefore no sound basis on which to elevate mere scribbles to the status of property. Ideas of personal genius perhaps rest on the property right, and not vice versa.

Corporate interests too can act in such a way as to cast doubt on the sanctity of a material interest in such as spiritual thing as creativity. All copyright owners know the dangers of overreach when enforcing exclusive rights against innocent infringers. We know that words and music are meant to be shared, not blocked; this is a cultural certainty ruthlessly exploited by platforms of mass participation. One might call this the revenge of Article 27(1): the corporate interests of the record company might deserve to be flouted, but the moral and material interests of the artist should be respected, a popular but unreconcilable discourse which plays out continually.

The old paradigm suited an era in which education, production, distribution, and of course markets, used to be constrained to elites. Now perhaps half of humanity takes all this for granted. The 21st century is an inversion of the age that gave us the old style of copyright, and needs a new myth.

So what new foundations might a new social contract for music rest upon? In an age of self-expression we should preserve strong rights for the creative individual. With so much of our public identity now digital it would seem absurd to allow the music we create and perform to be misappropriated; and those who suggest that authorship is too much of a technical challenge just need to consider the thousands of datapoints held about them in marketing databases. Of course your attribution rights can be respected, persistently, and if your identity can be known so can your economic interest.

But alongside this we need to acknowledge that the idea of the lonely genius has passed into history. In some ways we are recovering our pre-copyright communitarian approach to creativity. Certainly Shakespeare expected to borrow and lend, and to collaborate where it was expedient. Today’s digital creative and casual producer of recordings can be inherently collective and collaborative, layering and modifying the material more than shaping the void. We should find ways to support and reward participation with the future life of creative works rather than seeking to preserve the creator’s control. And perhaps we should recognise collaboration as a joint endeavour – one for all and all for one – rather than the sum of several contributions.

But alongside this we need to acknowledge that the idea of the lonely genius has passed into history. In some ways we are recovering our pre-copyright communitarian approach to creativity. Certainly Shakespeare expected to borrow and lend, and to collaborate where it was expedient. Today’s digital creative and casual producer of recordings can be inherently collective and collaborative, layering and modifying the material more than shaping the void. We should find ways to support and reward participation with the future life of creative works rather than seeking to preserve the creator’s control. And perhaps we should recognise collaboration as a joint endeavour – one for all and all for one – rather than the sum of several contributions.

There is a danger here that each item could end up dragging with it an infinity of attribution and reward, or that free riders could pile into and dilute the success created by others, just as search terms and hash tags get hijacked in today’s social media. Perhaps we need to consider degrees of creation and originality, with secondary creativity very much a subsidiary economic right. We have precedents. There is a separate right of arrangement in musical works which does not need to be exclusive; there are many thousands of private contracts made each year around the use of samples in new recordings, which could perhaps be collectivised.

Today we share, we participate, we have a strong sense of fairness, and we respect the individual. It’s important to recognise that we now have the digital tools to express all these ideas in our copyright framework, and even, thrillingly, to allow different copyright rules to co-exist and compete with each other for the affiliation of the best and most popular creators.