The Statute of Anne, enacted in England in 1710, opens with a statement of intent:

An Act for the Encouragement of Learning

I have argued elsewhere that it succeeded. Whether by the mechanisms intended, essentially the first modern copyright, or by serendipity as some would have it, Learning was Encouraged, universal literacy and scientific advance were achieved, and the profession of writing threw off the shackles of patronage to find an honourable place in the market. Printers moaned of course as writers got new pricing power, but made little impact on what was seen as a just and fair settlement.

Queen Anne making laws

All in all it was a very busy Act of Parliament. And worth reading from time to time in an age when many people think that copyright is a tool to impede learning by preventing writing, withholding access, and inflating prices. Today we benefit from the public domain, and lively and diverse markets for old and new books, plus a public library system (albeit one under stress), and for those who can afford it digital access to writing of all kinds.

But today’s faultlines are very visible. Instead of printers laboriously setting type, the new publishers are massive and almost instant copying machines, whose advertising engines are making unaccountable and unattributable money from the efforts of writers and creators. This widespread abuse is protected by a kind of enforced pseudonymity, which weakens not only the bonds between identity and authorship, but also our ability to hold each other accountable for our words and actions. And if creativity is flourishing on the horizontal axis, on the vertical, among the undoubted gems there is a viral outbreak of plagiarism and shallow re-use.

So where the deficit at the start of the 18th century was a self-regenerating engine for learning, at the start of the 21st century we are looking at a deficit of civil discourse and authentic creativity.

The Lord Keeper of the Great Seal.

It takes an historical imagination to understand why a late 17th scholar or parliamentarian would think that an Act to create copyright would encourage learning. The argument presented runs thus: Printers had been taking liberties, not asking permission before printing and reprinting, nor sharing the money they were making with writers. The lawmakers wanted to give writers a tool to negotiate a better deal with printers, and redress against infringements of their economic and reputational interests in their writings.

Alongside the private interests of writers, the public interest was clearly represented in the text and new rights and obligations the Act created. No protection for either the writer’s or the printer’s property could be obtained without a gift to the public of three copies each to the most established libraries of the day. The Act also formalised the public domain, by setting limits on the term of protection. The public interest was further advanced by the establishment of a register of works, under rules which allowed open inspection by anyone who cared to look.

The Act also added price control; if you thought a book was too expensive you could complain to any of a long list of authorities, including the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal and the Archbishop of Canterbury, who could decide what the fair price should be.

So, here’s an attempt to frame a Statute for the 21st century. Excuse me while I adjust my wig…

An Act for the Encouragement of Civil Discourse and Creativity by Vesting the Control of any Representation of Identity; and of the Use or Reuse of any Texts Images Sound Recordings Videos or any other Materials that may be Captured Copied and Transferred on Digital Services and Platforms; in the Person Represented by that Identity, and in the Original Creator of those Materials, during the times therein mentioned.

Whereas Digital Services and Platforms have of late frequently taken the Liberty of enabling and encouraging the Original Creations of one Person to be copied by another Person without Notice or Permission from the Creator; and in Flagrant Disregard of Common Courtesy allowed one Person to masquerade as Another while denying any Person the Ability to be identified as the Authentic Creator of what they have made; and of allowing and enabling Anonymous Messages to be sent in both Public and Private preventing any Redress for Abuse or Plagiarism of the Counterfeiting of Works of Art and Literature and Music; to the Detriment of Writers, Artists, Musicians, and Others who live by selling Copies of their Creations; and to the Great Detriment of Civil Discourse between People; May it be Enacted that the True Identity of each Person as they are Represented on such Digital Services and Platforms, and the Authentic Origination of any of Such Materials as they Create or Make, and any Permissions and Notifications about uses of Such Materials shall be solely under the Control and Right of those Persons; and further that any Assignment of those Rights and Permissions to the Owners and Operators of Digital Services and Platforms shall be subject to Valuable Consideration and shall be Accurately Recorded, such Records being freely available to any Interested Person on Demand.

If the sceptics are right we might well be coming to the end of the efficacy of copyright in the encouragement of learning. Times have after all changed, and printing presses are daily becoming less essential to the dissemination of knowledge and the exchange of ideas. But even if they are right, three hundred years is a pretty good run for an idea of how law and markets needed to be shaped, and we can apply the same approach and sound thinking to the deficits we see in today’s lives as they are lived on digital platforms.

Today we need better ways to talk to each other in public, so that divisions move towards compromise rather than conflict. And we need support for creativity that is less at the whim of the owners of digital platforms, who can tweak whole classes of creators out of a living by tuning an advertising algorithm or changing some monetisation rules; and whose incentives are diametrically opposed to authenticity and originality of content if it gives the creator stronger pricing power. We should recognise a common interest in getting this right for the next three hundred years. Those 17th century printers moaned and whined about the enfranchisement of writers, but profited handsomely from the encouragement of learning that copyright brought.

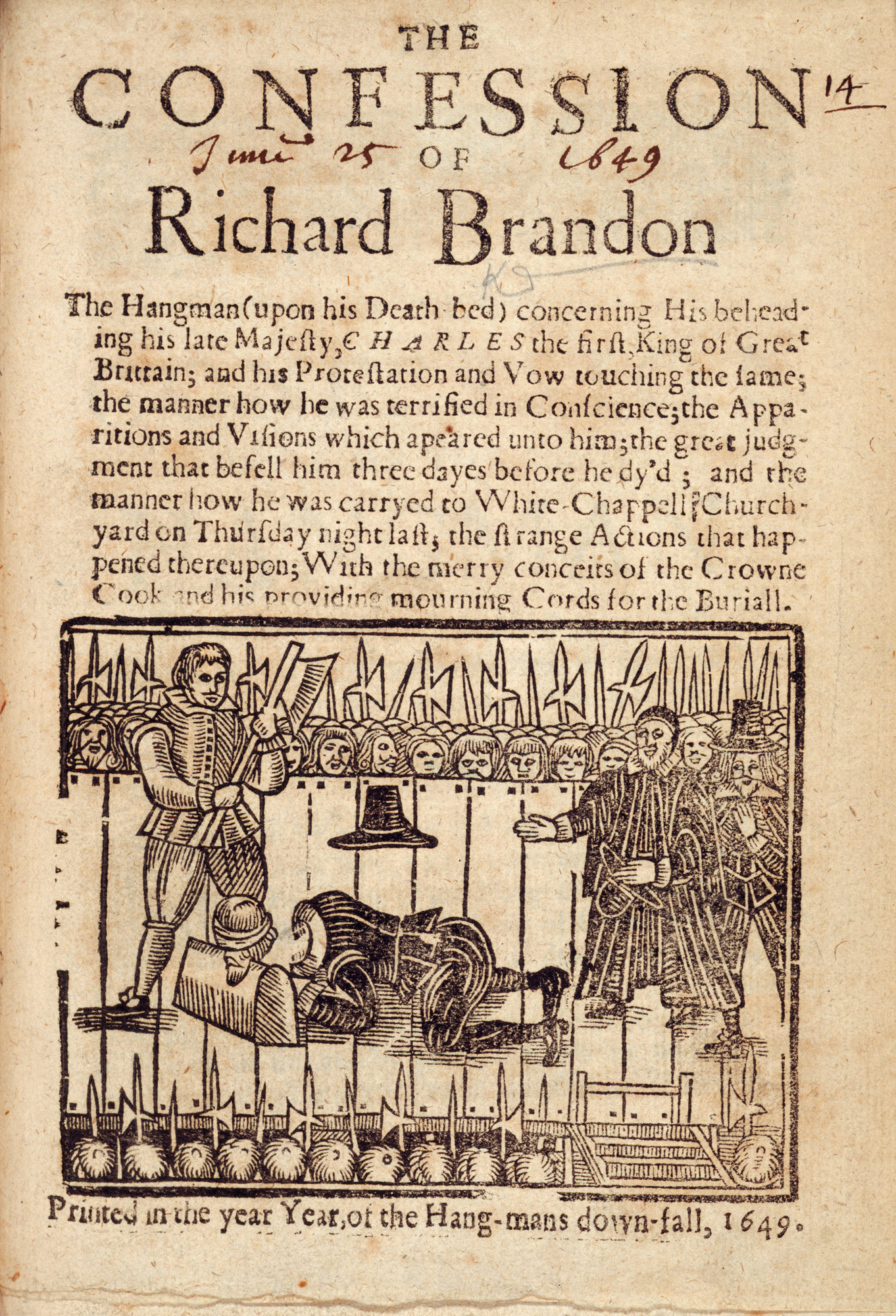

Other myths more prosaically bind copyright to printing monopolies and exclusivities granted by the 15th century Venetian senate. In mid 17th England similar monopolies granted by the king rather lost their force. The English Commonwealth was a regime that shut theatres and banned dancing on Sundays, an authoritarianism which saw copyright as a tool of political control, perhaps spurred by fear of the power of the pamphlet which had played so effective a part in the breakdown of the old order.

Other myths more prosaically bind copyright to printing monopolies and exclusivities granted by the 15th century Venetian senate. In mid 17th England similar monopolies granted by the king rather lost their force. The English Commonwealth was a regime that shut theatres and banned dancing on Sundays, an authoritarianism which saw copyright as a tool of political control, perhaps spurred by fear of the power of the pamphlet which had played so effective a part in the breakdown of the old order. But alongside this we need to acknowledge that the idea of the lonely genius has passed into history. In some ways we are recovering our pre-copyright communitarian approach to creativity. Certainly Shakespeare expected to borrow and lend, and to collaborate where it was expedient. Today’s digital creative and casual producer of recordings can be inherently collective and collaborative, layering and modifying the material more than shaping the void. We should find ways to support and reward participation with the future life of creative works rather than seeking to preserve the creator’s control. And perhaps we should recognise collaboration as a joint endeavour – one for all and all for one – rather than the sum of several contributions.

But alongside this we need to acknowledge that the idea of the lonely genius has passed into history. In some ways we are recovering our pre-copyright communitarian approach to creativity. Certainly Shakespeare expected to borrow and lend, and to collaborate where it was expedient. Today’s digital creative and casual producer of recordings can be inherently collective and collaborative, layering and modifying the material more than shaping the void. We should find ways to support and reward participation with the future life of creative works rather than seeking to preserve the creator’s control. And perhaps we should recognise collaboration as a joint endeavour – one for all and all for one – rather than the sum of several contributions.